Insight, inspiration and education

Understanding how the financial system and banking industry works can help us to get the most out of our savings and investments. Here our founders and partners share some of their knowledge.

Who can handle 2 percent interest?

Happy New Year everyone!

Over the break, I finally found time to read The Price of Time by Edward Chancellor – a book about why low interest rates keep getting us into trouble. What a great read.

If you have even a passing interest in money, saving, investing, or why financial booms and busts keep repeating, this book is sublime. For an interest rate tragic like me, it was pure beach-time bliss.

John Bull cannot stand 2 percent

In the book, Chancellor devotes an entire chapter to Walter Bagehot, the 19th-century journalist and editor of The Economist, and his famous line:

“John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand two per cent.”

John Bull wasn’t a real person. He was a recurring character Bagehot used to personify the everyday saver throughout English financial history. But Bagehot’s point was simple:

Interest rates below 2% are neither natural nor sustainable.

And when rates get that low, history suggests things start to go pear-shaped.

New Zealand just crossed this line (again)

But, to give this idea a uniquely New Zealand flavour, let’s instead call her Jenny Jandals.

Jenny works hard, saves sensibly, and mostly just wants her money to be safe and accessible. History suggests she can live with the envy of seeing sharemarkets racing higher. She can also handle bouts of market turmoil, knowing her low-risk saving strategy is designed to protect her when things get messy.

But when rates fall below 2%, history shows that even sensible people like Jenny often begin to take more risk with their money. Not because they’re reckless, but because the incentives have shifted. Suddenly, she faces a tough trade-off:

1. Stick to her guns and watch her savings effectively be inflated away, or

2. Take on more risk, perhaps in share markets or property, and hope the timing works out.

Neither option is particularly appealing – yet those are the choices low interest rates pose.

Forewarned is forearmed

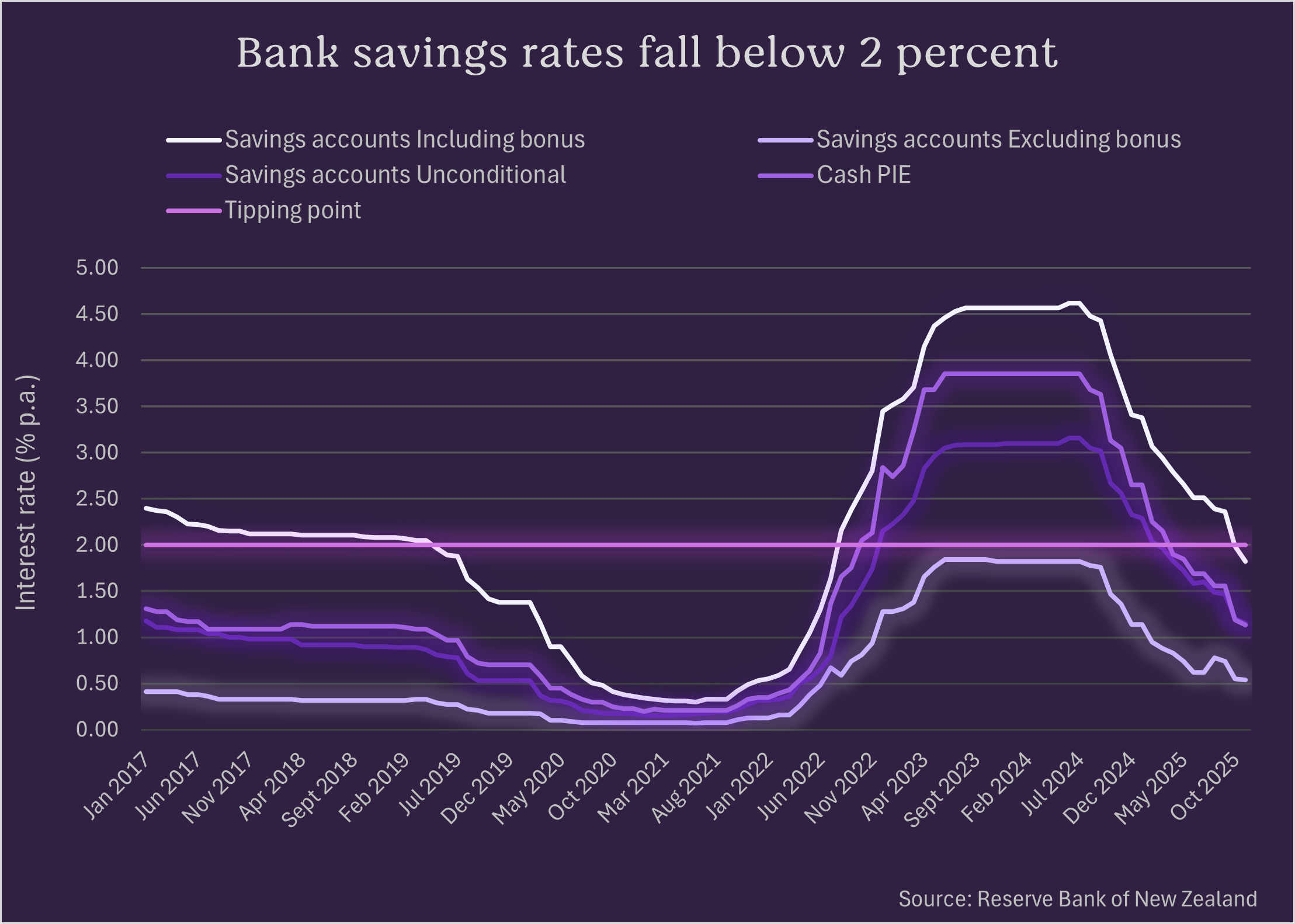

This is not a prediction of a share market crash, nor a warning against long-term equity investing. But with bank deposit rates now back below 2% (see chart below), my worry is that savers will once again be pushed toward risk in their search for returns.

Which probably explains why my social feed is suddenly full of fund manager ads like “Term deposit returns giving you FOMO?” or offering solutions for “How savers can stop their accounts being eroded by inflation.”

It doesn’t take Sir Peter Beck to see what’s going on. They’re trying to entice Jenny into taking more risk with her money – at precisely the moment she’s most susceptible to the idea.

Take the path of least regret

There’s nothing clever about chasing returns just to keep up. And there’s nothing boring about keeping your money aligned with what it’s actually meant for.

If you can’t afford, or simply can’t stomach, your balance falling – or even if you can handle some volatility but may need the money within the next couple of years – do yourself a (potentially huge) favour and think twice before taking more risk with your savings.

History has been remarkably consistent on this point.

Get the full picture before taking more risk

For someone like Jenny – who just wants her money safe, accessible, and doing something sensible – she can find a great table for comparing bank and non-bank savings products here.

It’s a useful reminder that while many headline bank rates have slipped below 2%, not all low-risk options have passed Bagehot’s tipping point.

Because for Jenny, it’s all about making sure she can still handle the jandal even when financial markets get a bit slippery.